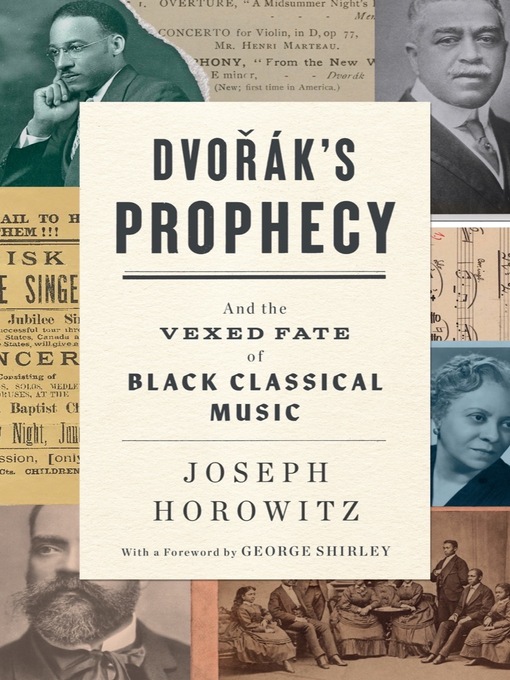

A Kirkus Reviews Best Nonfiction Book of 2021

A provocative interpretation of why classical music in America "stayed white"—how it got to be that way and what can be done about it.

In 1893 the composer Antonín Dvorák prophesied a "great and noble school" of American classical music based on the "negro melodies" he had excitedly discovered since arriving in the United States a year before. But while Black music would foster popular genres known the world over, it never gained a foothold in the concert hall. Black composers found few opportunities to have their works performed, and white composers mainly rejected Dvorák's lead.

Joseph Horowitz ranges throughout American cultural history, from Frederick Douglass and Huckleberry Finn to George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess and the work of Ralph Ellison, searching for explanations. Challenging the standard narrative for American classical music fashioned by Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein, he looks back to literary figures—Emerson, Melville, and Twain—to ponder how American music can connect with a "usable past." The result is a new paradigm that makes room for Black composers, including Harry Burleigh, Nathaniel Dett, William Levi Dawson, and Florence Price, while giving increased prominence to Charles Ives and George Gershwin.

Dvorák's Prophecy arrives in the midst of an important conversation about race in America—a conversation that is taking place in music schools and concert halls as well as capitols and boardrooms. As George Shirley writes in his foreword to the book, "We have been left unprepared for the current cultural moment. [Joseph Horowitz] explains how we got there [and] proposes a bigger world of American classical music than what we have known before. It is more diverse and more equitable. And it is more truthful."